Youth Mental Health: What Epidemiological Research Says in France and Europe

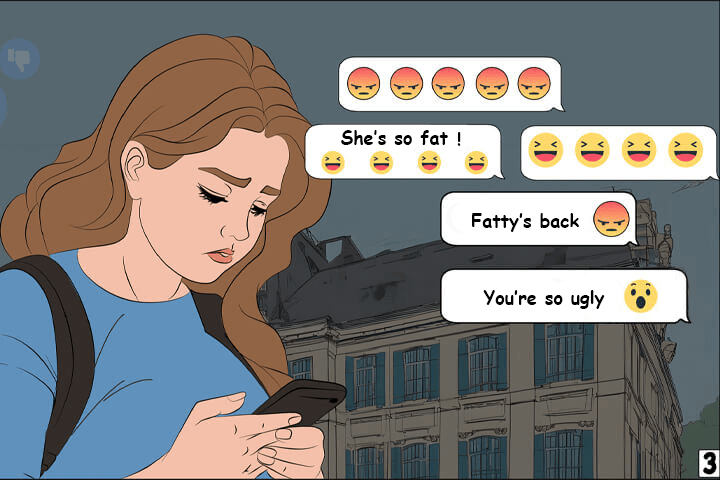

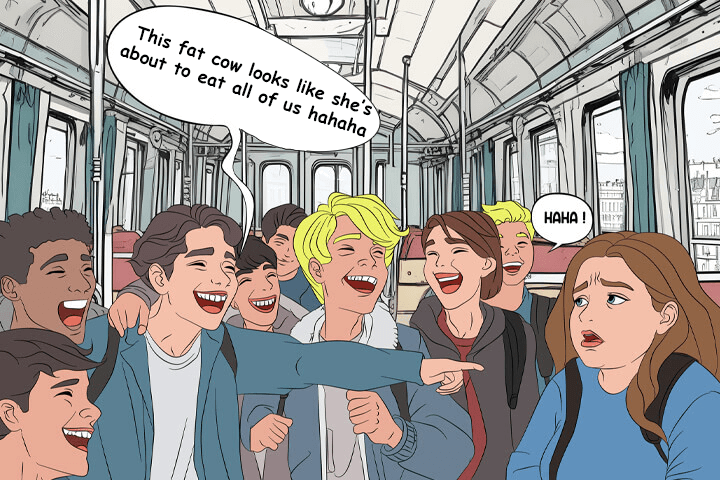

Youth mental health has become a major concern for health authorities, educational institutions, and families. Epidemiological data published in France and across Europe paint a worrying picture, showing an upward trend in mental health disorders among adolescents and students. This dynamic, already underway before the health crisis, has significantly intensified since the COVID-19 pandemic.

A steadily increasing prevalence

According to a study published in 2023 by Santé publique France, nearly one in four adolescents shows signs of moderate to severe psychological distress. This proportion rises to 30% among girls aged 15 to 17, compared with 16% among boys of the same age. The same study also reports a significant increase in depressive and anxiety symptoms since 2017.

Data from INSEE confirm this trend. In its 2024 report on young people’s living conditions, the institute highlights a continuous deterioration in the psychological well-being of those aged 15–24. The increase in feelings of loneliness, social isolation, and stress related to studies or career orientation is particularly striking.

The impact of the health crisis: a lasting effect

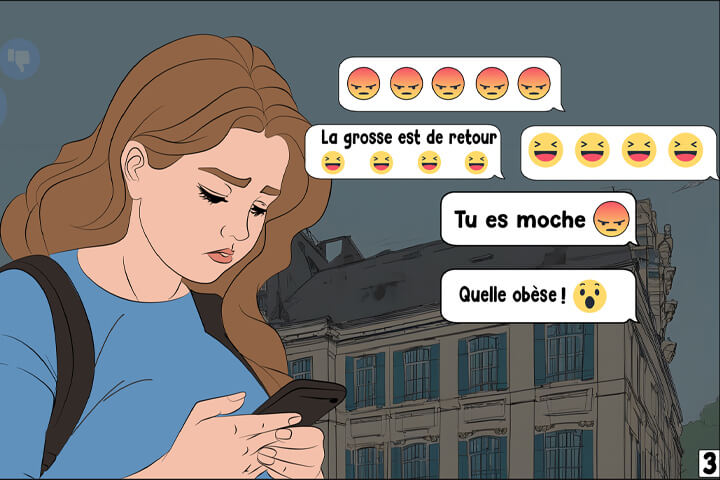

INSERM, in a literature review published in 2022, highlighted the lasting impact of the pandemic on young people’s mental health. Successive lockdowns, school closures, the loss of social reference points, and anxiety about the future were identified as aggravating factors. The risk of depression among adolescents doubled between 2019 and 2021.

The European Commission, drawing on data from Eurostat and the Health at a Glance – Europe program, reports similar trends across several countries, including Germany, Spain, Italy, and the Netherlands. On average, nearly 20% of young Europeans report frequent psychological distress, with peaks in major urban areas and among socially vulnerable populations.

Early and persistent disorders

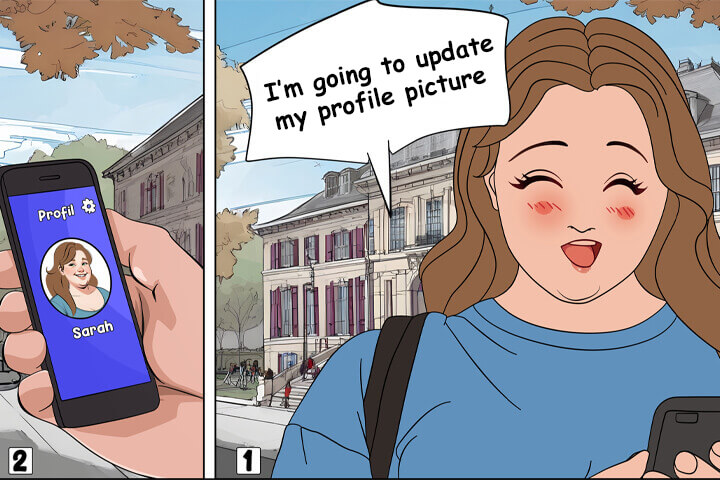

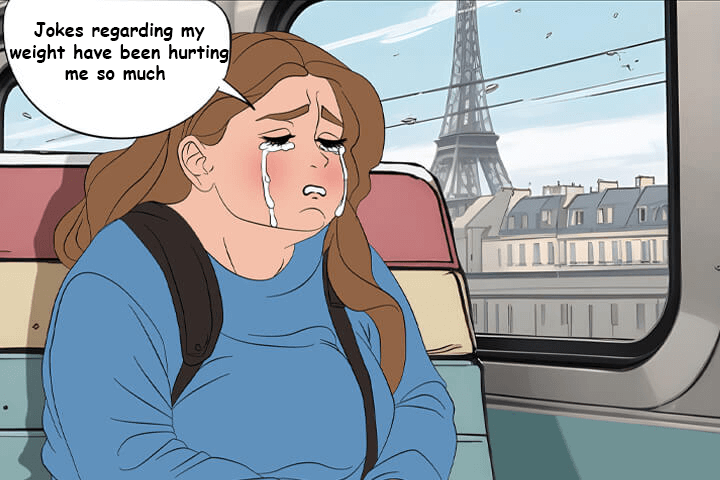

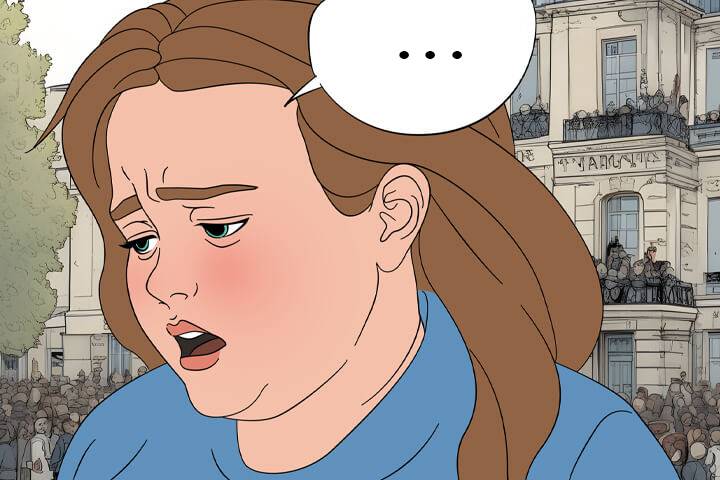

The most common mental health disorders among young people are anxiety disorders, depression, eating disorders (EDs), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and suicidal behaviors.

According to research coordinated by the French National Authority for Health (HAS), 50% of mental disorders appear before the age of 14, and 75% before the age of 24. This highlights the importance of early detection and follow-up from the very first symptoms.

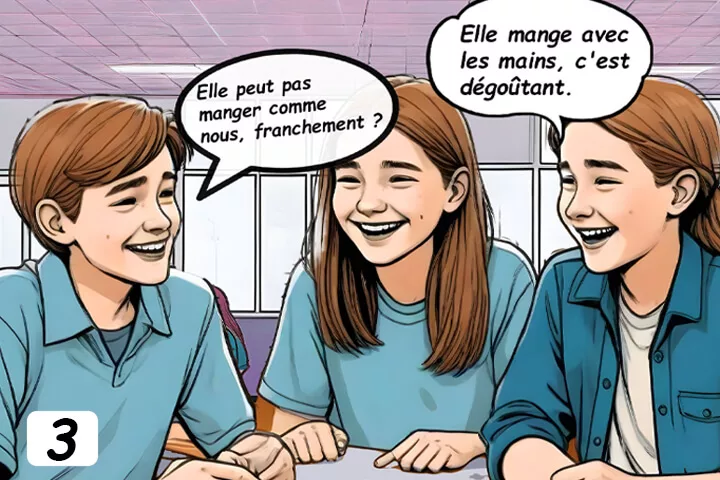

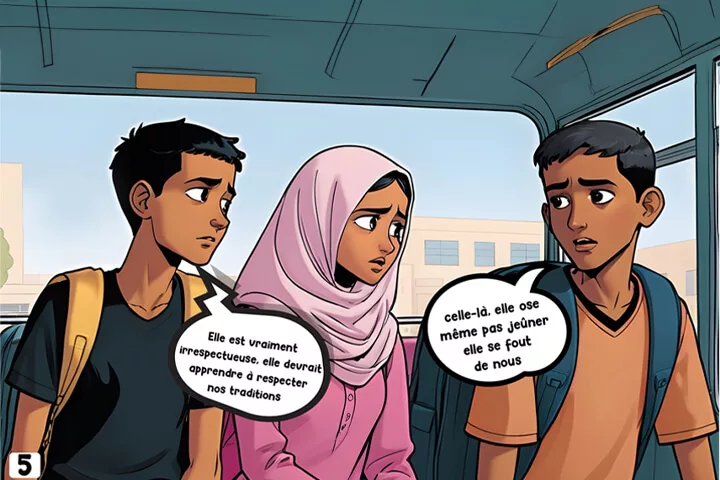

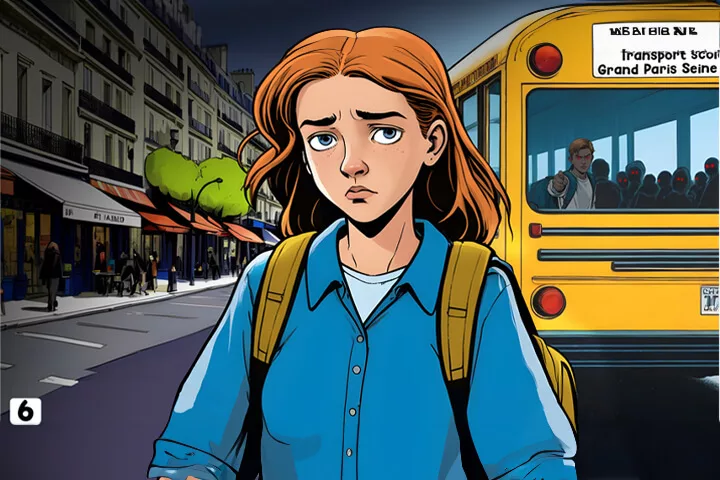

Cross-referenced data from Santé publique France and the National Observatory of Student Life (OVE) show that young people’s mental health is strongly correlated with income level, family situation, and place of residence. Scholarship students, those living alone, or those housed in collective residences are significantly more exposed to depressive disorders. In schools, institutions classified as REP or REP+ concentrate a higher number of cases of psychological distress.

Access to care: coverage still insufficient

Despite rising needs, the supply of mental health services for young people remains very unevenly distributed. In 2023, a report by the Defender of Rights highlighted the difficulties in accessing school psychologists, consultations in CMPP (medico-psycho-pedagogical centers), and psychiatric follow-up in universities. The “Santé Psy Étudiants” scheme, introduced in 2021, has proven useful but remains limited in both duration and coverage.

At the European level, countries such as Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands have implemented more integrated “mental health in schools” systems, bringing together teachers, psychologists, and social services.

Towards stronger public policies to protect youth mental health

In France, several institutions are calling for stronger coordination between educational and health policies. The 2023–2028 National Mental Health Prevention Plan identifies young people as a priority group, with objectives including the training of educational staff, early screening, and community support. However, feedback from the field indicates that implementation remains slow and uneven.

Conclusion

Epidemiological research provides undeniable evidence: youth mental health is in decline and requires a structured, coordinated, and lasting response. Both French and European data converge on the same warning: mental health disorders are no longer marginal among 15–24-year-olds. It is time to make this issue a political, educational, and social priority, moving beyond temporary measures or statements of intent.