Humor and school bullying: understanding the boundary between joke and harm

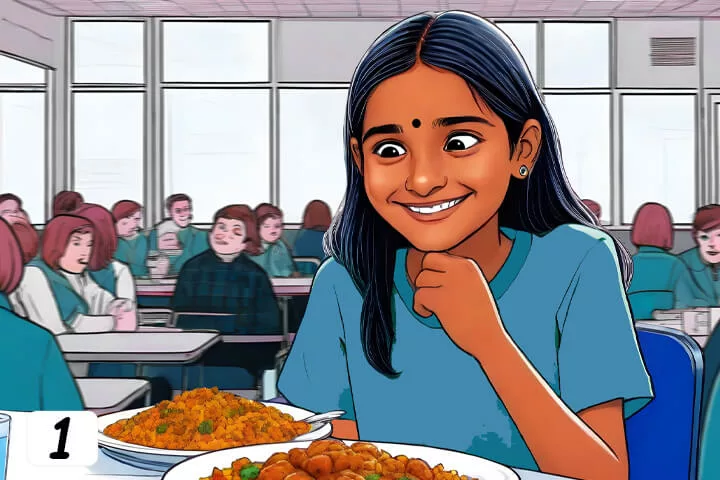

Humor plays a central role in the social lives of children and adolescents. It helps create bonds, lighten the atmosphere, and strengthen camaraderie among peers. However, humor can also become a tool of domination and violence when it crosses the line between a shared joke and imposed humiliation. In the school context, this boundary is sometimes difficult to perceive, both for students and adults. It is this ambiguity that makes the relationship between school bullying and humor particularly complex to analyze and prevent.

When humor turns into bullying: understanding the nuance

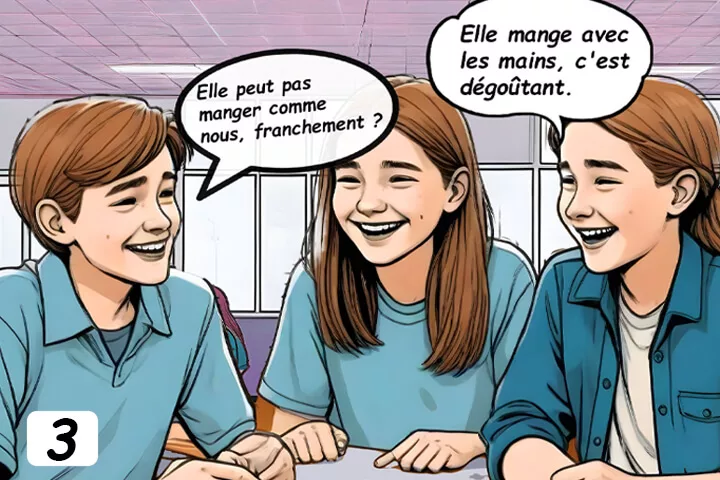

It is common to hear students say:

“But it was just for fun!”

“He has no sense of humor…”

“We’re just teasing, that’s all.”

Yet behind what is presented as child’s play or a simple joke, there can sometimes be repeated violence that psychologically weakens the victim.

The key difference between humor and bullying lies in consent.

A joke is only funny if it makes everyone laugh, including the person targeted. Once one of the participants feels hurt, humiliated, or isolated, the situation moves out of the realm of humor and into aggression.

Bullying begins when:

Mockery becomes repetitive and targeted;

The humor always targets the same person;

Bystanders laugh, but the victim withdraws;

The joke damages the student’s image within the group;

The “joke” is used to assert power or domination.

Humor can therefore be a means of violence, especially when veiled in irony, sarcasm, or double entendre.

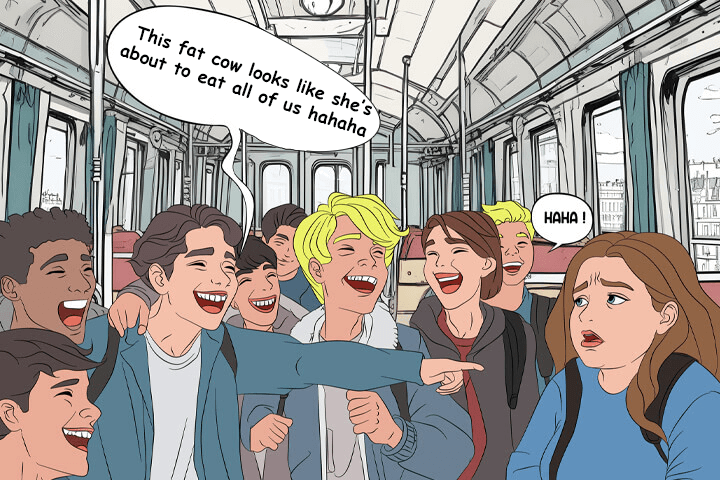

Why is humor so prevalent in bullying situations?

Humor has immense social power. It can unite and create a group, but it can also exclude. Some students use this power to reinforce their status or to mask their own vulnerabilities.

A tool of social domination

In a group, the one who makes others laugh often holds a valued position.

This is why some bullies use humor as a way to assert their influence. The laughter of others then becomes fuel: the more they laugh, the more the teasing intensifies.

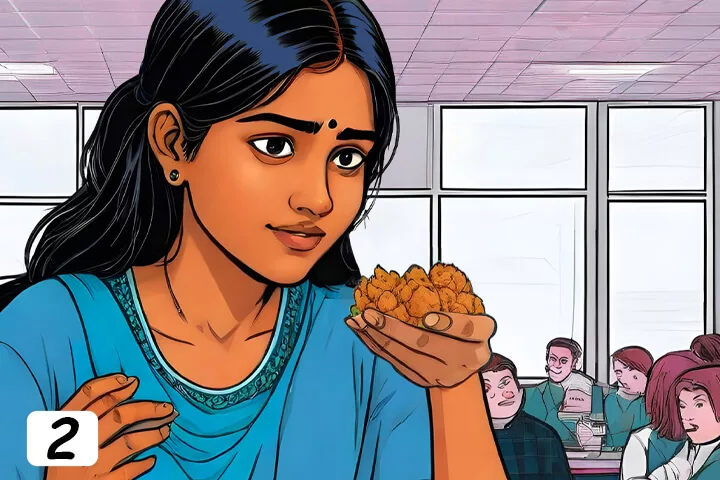

A form of violence that is harder to detect

A clear insult or a physical hit is generally easy to identify immediately.

However, hurtful humor hides behind:

Irony,

Parody,

Mocking nicknames,

Humiliating “running gags,”

Altered videos or photos.

For adults, it can be difficult to intervene because the violence seems less obvious. And for the child victim, it becomes complicated to report attacks that do not appear “serious.”

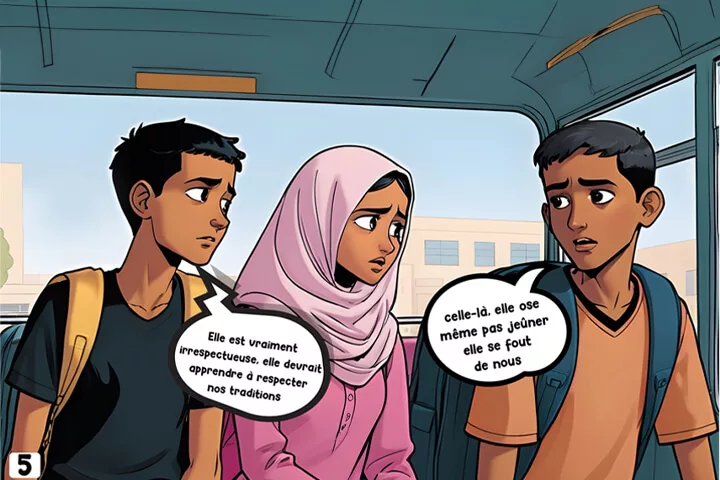

A way to downplay the impact

Students who hurt others through humor often use the argument, “It wasn’t mean,” which allows them to avoid consequences and shirk responsibility. This trivialization makes intervention more delicate and increases the guilt of the targeted child, who may wonder if they are “too sensitive.”

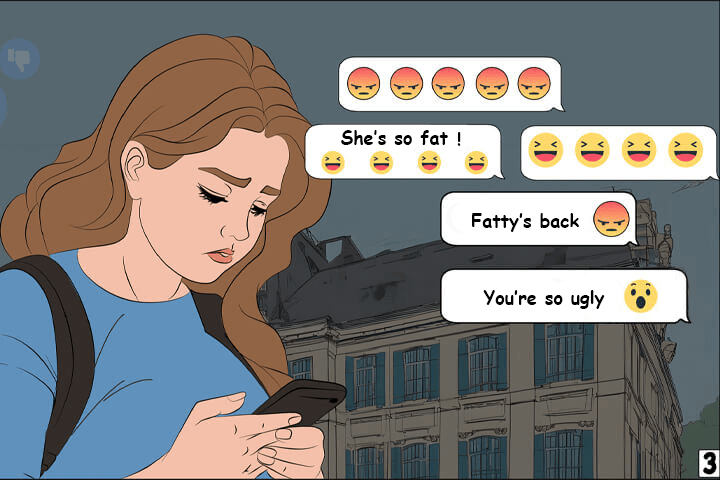

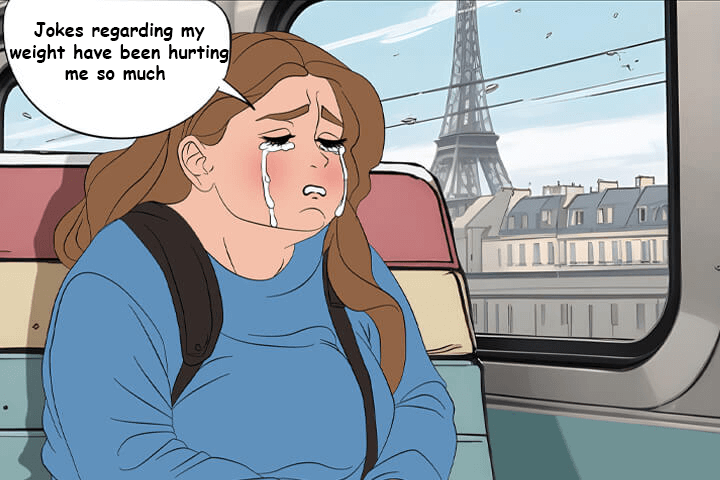

Humor, sensitivity, and guilt: the spiral of doubt in the victim

When a child becomes the target of repeated jokes, they can enter a state of emotional confusion. They are told they lack a sense of humor, that they don’t understand, or that they are overreacting. They then begin to doubt their own feelings, which is one of the most destructive psychological mechanisms in bullying.

Gradually, they may:

Lose self-esteem;

Accept humiliations to avoid “making a fuss”;

Force a laugh to avoid appearing weak;

Believe that the teasing reflects reality about themselves;

Isolate themselves for fear of being targeted again.

This gap between what they feel and what the group validates creates fertile ground for anxiety, depression, and school phobia.

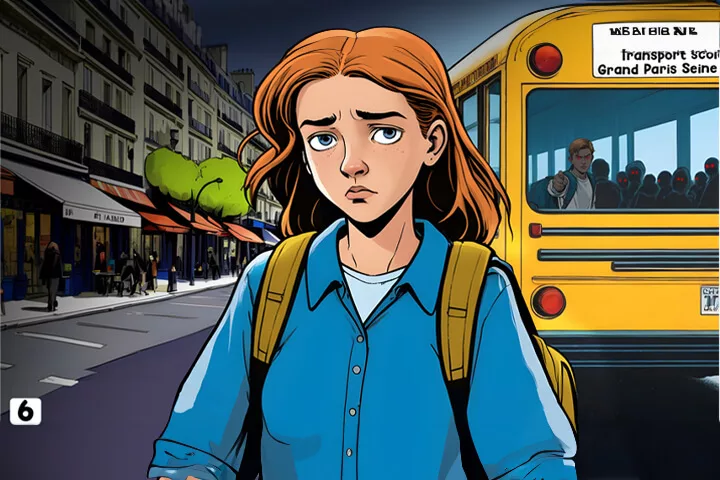

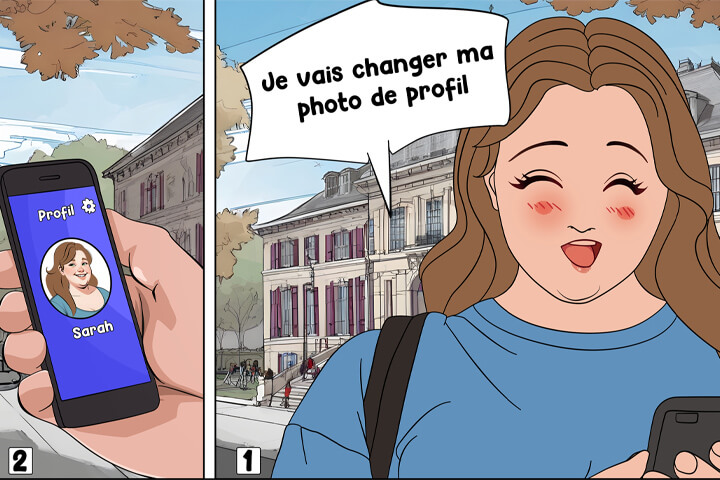

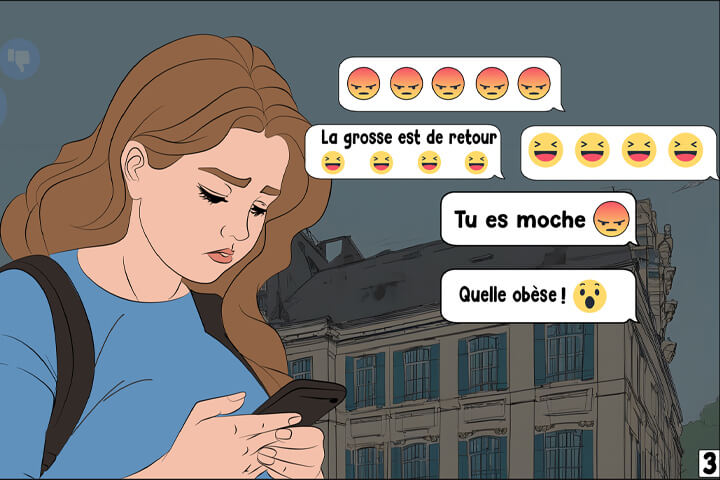

Humor as symbolic violence: a phenomenon amplified by digital media

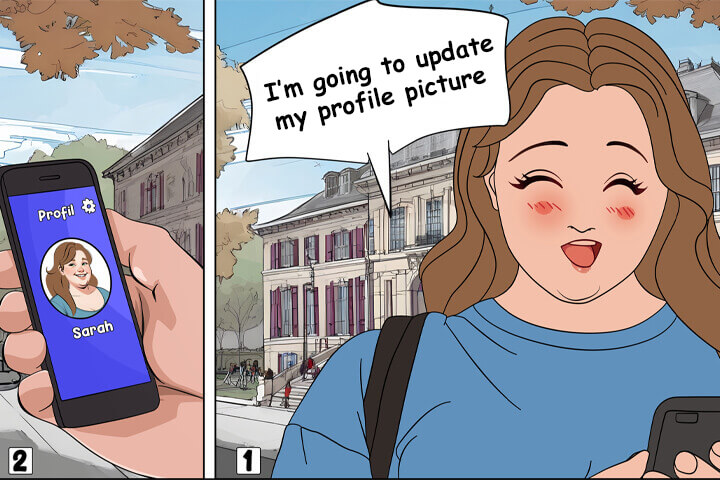

With social media, the line between humor and bullying becomes even blurrier. A simple meme, photo edit, or altered video can spread very quickly, reach dozens of students, and cause lasting humiliation.

Digital media amplifies:

The speed of dissemination;

The potential audience;

The anonymity of the perpetrators;

The difficulty of removing content.

A student can become the target of “trolling” or a “viral joke” with no way to stop its spread.

How to teach children to distinguish between humor and bullying

It is essential to educate students, from a young age, to recognize the limits of humor. This involves several approaches.

Fostering empathy and emotional intelligence

Children should learn to ask themselves:

Does the targeted person also laugh?

Could this joke be hurtful?

How would I feel if this were done about me?

Developing this reflection is crucial to prevent misuse.

Reminding that humor is never an excuse to hurt

Teachers and educators must make it clear that humor is not a right to belittle or humiliate. “Sarcasm” or “irony” is not a moral shield.

Encouraging communication

A child should feel empowered to say:

“This joke makes me uncomfortable.”

“I don’t like being spoken to this way.”

“This isn’t funny to me.”

Learning to set boundaries is essential.

Raising group awareness and valuing active bystanders

Many students laugh out of conformity. Working on the power of the group and the importance of defending a victim is essential to create lasting behavioral change.

Humor as a positive tool: restoring joy and self-deprecation

While humor can hurt, it can also help children overcome difficulties when used kindly. Joking together, laughing at the same joke, and practicing self-deprecation respectfully can create a warm and safe school environment.

The goal is therefore not to eliminate humor, but to learn to use it as a tool for connection rather than as a weapon for social harm.

Conclusion: humor should never mask violence

Bullying expressed through humor is particularly insidious because it hides behind seemingly harmless and socially acceptable appearances. Yet its effects are just as serious as those of direct physical or verbal bullying. Teaching children to distinguish between a joke and an attack, to listen to their own emotions, and to respect the feelings of others is essential for building healthy and caring relationships.

Humor should remain a space for joy and connection, never a tool for domination or suffering.